Aggrieved video copyright owners occasionally e-mail CBL Translations asking for assistance in translating Youku’s official, yet mistranslated, copyright infringement form. We feel that this information should be publicly available, and you should not need to hire a translator to figure out what Youku’s translators are trying to say on their form. In this article, we will identify how and why Youku failed so spectacularly in its legal localization and walk you through how we would analyze this linguistic task.

What is legal localization?

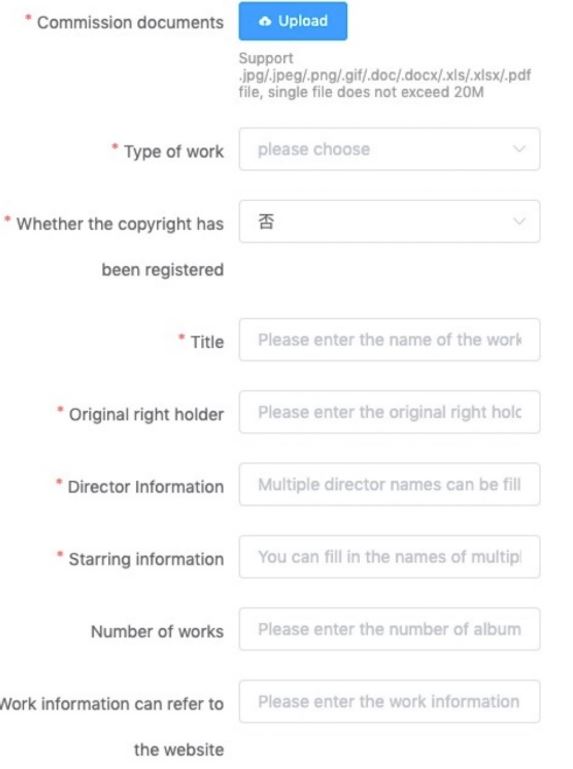

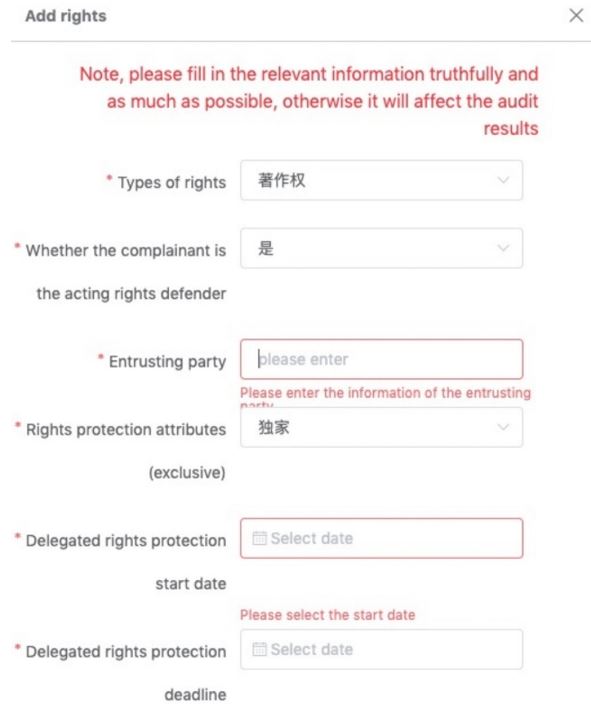

Youku’s general counsel office no doubt worked hard on the copyright form to ensure that every kind of intellectual property right is protected, only for the translation to wreck it, as shown below. Often, it’s actually lawyers who translate their own firm’s legal forms into something totally different. These absurd mistranslations often raise several questions about the form among video copyright owners. We’ve received e-mails pointing out that “delegated rights protection deadline” causes a lot of confusion because no delegations are involved. “Starring information” also confuses video creators, who generally have no idea what to fill in. Ultimately, all this leads to is frustrated copyright holders and a lot of good Chinese legal work going to waste. Below, we’ll answer these questions about what these fields mean so frustrated copyright holders know how to fill in the Youku form.

Youku’s first big mistake was in using direct translation, when the form should have been processed through the legal localization process. Unlike with a standard translation, the Youku form should have been adapted to facilitate the platform’s goal of collecting legally relevant information. In this case, the English version should be organized differently to make it easier for the desired copyright infringement facts to be collected via the form. The first step for a legal localization is to clarify what these expressions mean, which helps the localization engineering team design the best adaptation.

What is a “delegation deadline”?

The Chinese word translated confusingly here as “delegation” is actually referring to the familiar legal concept for the “authority” of an agent to act on a principal’s behalf. A clear description of authority is given in Restatement (Third) of Agency § 2.01:

“An agent acts with actual authority when, at the time of taking action that has legal consequences for the principal, the agent reasonably believes, in accordance with the principal’s manifestations to the agent, that the principal wishes the agent so to act.”

So, in our interpretation, Youku is simply seeking authorization to look into copyrights on your behalf for a specified period of time, after which you would expect an answer from them before having to resort to third-party assistance. While English has a variety of terms to describe the single concept of authority, such as power of attorney usually given to a non-attorney, or a retainer for an attorney, the Chinese language uses one word to describe the three concepts of agent, principal, and authority. That word is weituo (委托), a Chinese legal concept that has been very clearly defined by interpretations issued by the Commission of Legislative Affairs of the NPC Standing Committee, which we have translated for ease of understanding the concepts:

“Section 397 A principal may grant an agent either a special power of attorney to carry out a limited set of actions, or general power of attorney to perform any act on their behalf.

[Interpretation] This section provides for the scope of the authority granted.

An agent has the authority to take action as designated by the principal. The Power of Attorney is classified as either a special or general Power of Attorney based on the scope of authority granted to an agent.

The distinction between a special and general Power of Attorney enables agents to understand what acts may be performed on behalf of a principal. Furthermore, this makes the identity of and authority granted to the agent known to third parties, thus enabling them to purposefully choose and execute private contracts to prevent unnecessary disputes arising from ambiguous agency authority. In the event of a dispute, this facilitates the determination of the interested parties’ liability based on the scope of authority.”

Original Chinese here.

Semantically, what the Chinese legal concept weituo (authority) maps to in English law depends on the context. If you are the “authority giver,” then you are the principal. If you are the “authority receiver,” then you are the agent. Authority is very similar to a game of hot potato; the hot potato never changes but holding onto the potato defines who you are and whether you will get fired if it gets too hot. The above authority also distinguishes a kind of “special authority,” which really just refers to attorneys and powers of attorney:

“A special Power of Attorney allows the principal to grant an agent the authority to perform acts on their behalf. It generally includes 1. the sale or lease of real property or perfection of a security interest in real property 2. donations 3. reconciliations; 4. litigation; and 5. arbitration. [..] An agent may do anything lawful to pursue the principal’s best interest as required.”

Those familiar with agency agreements will recognize property transactions as a kind of Power of Attorney, which are common for corporate officers or persons making real estate transactions. Lawyers will recognize the last three situations as being covered by a Retainer Agreement. Thus, we would usually translate a document giving authority to sell the property to a corporate officer as a Power of Attorney, and a document related to retaining an attorney or a similar matter as a Retainer Agreement.

Youku’s form is not set up to directly translate the concept of weituo (authority) word-for-word. Their translators, therefore, attempted to resolve the impossibility of this task by using a direct translation approach that translated the same word in three different ways: entrust, delegate, and commission. A more logical approach would be to use a single word for the Chinese legal concept by consolidating information from those lines to the words “on your behalf.” For example: “Please tell us who is requesting the copyright investigation and when this must be completed on your behalf” followed with blanks for names and dates.

What is Youku’s Starring Information? (Do they need a gold star?)

Youku’s request for “Starring Information” has nothing to do with starring or stars, and the word “star” does not even appear in the original Chinese. Rather, this appears to simply have been a wild guess by their translators. Youku’s attorneys are instead trying to ask who in the video has a protectable right to likeness. A Chinese civil rights enforcement regulator’s periodical journal provides the following guidance on how actors can protect their rights on platforms such as Youku:

“Journalist: Reproducing a film still without authorization infringes upon the filmmaker’s or producer’s copyright. It also infringes on the appearing actor’s rights. So, would they be able to sue for copyright infringement? […]

Zhong Lun Law Firm attorney Hai Shu: Actors cannot sue for copyright infringement, but can nonetheless claim for infringement of their likeness rights. By likeness rights, we mean a natural person’s individual interest held in their personal physical image as represented through a medium.” (Original Chinese source here.)

Like other legal systems, China has a very robust definition of what a person’s likeness entails and when it is protectable. The boundaries of what is protectable are different from those of the English right to likeness, but in essence, remain under the same concept with which attorneys are quite familiar. An academic article published in China describes it as follows:

“Likeness refers to definite images of a natural person shown in videos, sculptures, paintings, and identifiable media forms; it is a definite representation of a natural person’s appearance through a definite media. Likeness rights refer to the rights held by natural persons to make, use, and publicly disclose their likeness…Likeness is any objective representation of definite external images of a natural person through definite media, and external images refer to a natural person’s appearance based on their thoughts and emotions. Therefore, whether a film still, cartoon image, silhouette, or other medium is identifiable is key when judging whether it is protected by likeness rights.” (Mandarin source here.)

Thus, Youku should have simply asked for whoever appears in the video to be listed in the form, and this is how it should be filled in. However, they are only concerned with the performers, interviewees, and such; this is because Chinese cases have held that an incidental appearance of a pedestrian walking by does not establish a protectable right to likeness.

How did the translators go so wrong?

For this question, we engaged young and up-and-coming Chinese translators who have experience working with so-called “senior” translators to shed some light on the work process still being billed as “expert.” This is the response we received:

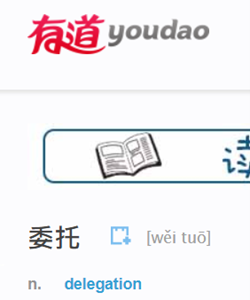

“The answer lies in their sole reliance on machine translations and bilingual dictionaries. If you type the Chinese equivalent of “starring information” into Google Translate, you will get the exact same result as that in the form. As for the “delegated rights protection start date,” more supposed work was involved. After realizing that Bing Translator translates the Chinese phrase as “delegate rights activists start day,” while Google translates it as “start date of entrusted rights protection,” the translator likely hesitated. They then resorted to Youdao Dictionary, one of the most popular online dictionaries in China. Youdao Dictionary translates “weituo” as “delegation.” Therefore, the decision was subsequently made to use a combination of all three for what they thought was the best translation.”

“The answer lies in their sole reliance on machine translations and bilingual dictionaries. If you type the Chinese equivalent of “starring information” into Google Translate, you will get the exact same result as that in the form. As for the “delegated rights protection start date,” more supposed work was involved. After realizing that Bing Translator translates the Chinese phrase as “delegate rights activists start day,” while Google translates it as “start date of entrusted rights protection,” the translator likely hesitated. They then resorted to Youdao Dictionary, one of the most popular online dictionaries in China. Youdao Dictionary translates “weituo” as “delegation.” Therefore, the decision was subsequently made to use a combination of all three for what they thought was the best translation.”

Having non-translators do Chinese legal translation is also no solution to translation incompetence. These problems are common at even top law firms. Our university student researchers have investigated and found clear evidence of legal translations minimally distinguishable from wildly incorrect machine translation. Youku is not alone. In our surveys, almost all incidents of extreme translation negligence involve hiring uncertified translators untrained in the legal industry.

Conclusion

Copyright owners rightly feel Youku is responsible for their failure to make a coherent copyright claims process available to the public. However, I feel that Youku is also a victim in this matter as well, by untrustworthy and dishonest translators who said they could get the job done and produce great results. This kind of thing is all too common in the market today: a translation company offers sterling quality, but the actual result is incomprehensible to the reader and indistinguishable from a machine translator. We hope this article will help English speakers engage with Chinese companies to protect their intellectual property. If you have seen incoherent legal documents on Chinese company websites and need help deciphering them, please send us an e-mail and we’ll help however we can.