Outsourcers

Outsourcers are essential for the localization industry. Localizing a website is a matter of hiring a vendor to go out and find a sub-vendor in each of the 20 cou ntries being pursued localization. Where do lawyers go wrong here? They go out and hire outsourcers using the model Tucker outlined above. According to Tucker and in my own experience, these companies pool all of their language project managers into one division not separated by language or field; for example, when I worked in-house at New York’s biggest translation company, we had a 24-year old project manager responsible for a $1 billion+ federal corporate crime case but at the same time a wide variety of marketing and even scientific research matters. Legal translation makes up only a very tiny percentage of what an outsourcer using Tucker’s model does, so they use their very long and most importantly–existing–supply chains to fill legal orders, despite how this is totally inappropriate to these legal cases.

Instead of creating value at every step in the supply chain like they do for advertisers, the typical outsourcing model essentially takes a law firm’s money and lights it on fire. What tiny amount of money actually remains to buy Chinese translation services, which is typically 2-3% of the original amount, can only pay for people so dishonest, incompetent, and untrained that if you actually inquired how the work was being done, in many cases you would be liable for criminal fraud or serious legal malpractice. However, the outsourcer itself likely does not know who is doing the translations. The bread and butter of the outsourcing model are to take low-skill/no-skill matters like advertising copy, blog posts, software, and other consumer content to vendors in dozens of countries to get it translated into dozens of languages by hundreds of amateur freelancers overnight.

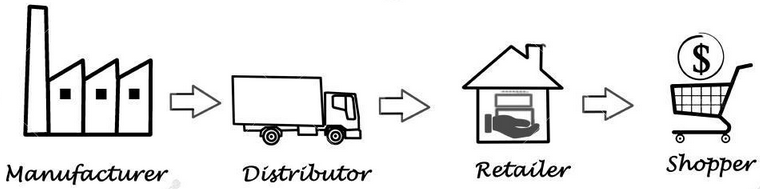

To put things in perspective, if you had a grocery list of thirty different things you needed to get before going home tonight—milk, bread, toothpaste, cold medicine, and so forth—where would you go? You would go to a supermarket, and they would use the following kind of supply chain to sell each of those thirty products to you all in one fell swoop:

Many would say that these companies steal value from legal matters, but much of the blame rests on the shoulders of the lawyers as well for finding an inappropriate provider. The grocery store style translation outsourcer’s managers must incur fantastic costs to spend many hours building a vast global supply chain in 3,000 language combinations in 200 specialties, for a half-million possible requests. Both the supply chain managers and salespeople must spend enormous effort before an hour can be spent on an actual project. Sales staff must spend countless hours explaining how localization works and what the options are to clients, to help them make the right decision. Then they must investigate, vet, test, and re-test each supplier. Thus, each available project management hour requires many additional hours of non-billable work. Moreover, just getting enough visibility to collect 10,000 resumes from Chinese translators in itself will cost millions of dollars in marketing and public relations spending.

Deploying such a vast advertising translation machine to do legal work would be an immense mismatch of skills and capabilities, but this is what many lawyers do.

Law firms often like to buy from one of the 50 or so largest outsourcers because they think a firm must be better if it is bigger. I would call this logic the “H&R Block Fallacy”: the fact a company is big makes its empty promises of expertise true. Nobody would think that H&R Block, which uses a McDonald’s approach to selling tax services, is on the same level as PWC or EY simply because it is a multi-billion dollar accounting service provider How can you tell that PWC and KPMG have real experts and H&R Block does not? If you go to PWC and look at their advisory services, you will immediately see pictures of the people who will advise you, the same as if you were visiting Skadden or White & Case’s website. Their peerless credentials are proof. If you go to H&R Block, you won’t see any experts listed because that’s not the substance of what the company offers. However, a lawyer suffering from the H&R Block Fallacy may very choose to rely on empty promises in the relatively unfamiliar languages field.

Core Business

Companies tend to outsource work that is not part of their core business. Localization and globalization are the core business of any very large translation company, one you would expect to have enough freelancers to do a large legal translation project—essentially acting as a kind of special advertising agency that helps brands and companies reach into foreign markets. For the core business, a translation agency may have hundreds or thousands of in-house employees handling the complicated technical and creative work needed to drive global advertising. Degree programs and courses of study focus dominantly on marketing and localization, which are fundamentally unrelated to the needs of a law firm. The in-house staff of these companies is not well positioned to tell if a document is translated correctly, thus making the outsourcer itself a target for fraud by the famously dishonest Chinese translators. Outside of their core business, these companies act as large sourcing agents and have long supplier lists.

Most small legal translation outsourcers have a different modus operandi. These companies may have just a dozen project managers but routinely handle projects with tens of millions of words every day. How do they do it? These companies just call someone up in China for a third of the rate you are paying them, and simply create a shared folder for all the documents you send them, which empty out into another company’s inbox. Their sole role is to put their branding on the project and apply a large markup. Generally, the work they get back is fake, but neither the company nor the client will investigate this issue too closely;

You might be wondering if these firms outsource to professional services firms. The answer is no. For a project suitable for experts, these firms would need to have a very high gross profit margin–often over 70%–which means that it would be unprofitable for them to hire a firm that specializes in doing high-quality work. Usually, an outsourcer will turn to a company in China that is skilled at fraud and thus can offer rock-bottom prices, selling translations that are just legitimate looking enough that the lawyers don’t check to see if they are fake, and ensuring the profitability of the outsourcer.

Capabilities of outsourcers

Outside their core businesses, the outsourcing divisions of translation companies focus on vendor management, that is, they look for temp agencies that provide translators and have a pretty good list of which companies are good and which companies are not so good around the world. This enables these firms to provide full-service sourcing, that is, no matter what the language or what kind of service is desired, they can find a supplier to source it from. The costs of maintaining a list of supplier corporations needed to do a globalization project are so expensive that persons within some of these companies have reported that administrative costs account for over 96% of the fees collected for projects in China. It’s expensive because you are paying for the ability to marshal thousands of temporary employees in any city in the world with any language skills in a matter of hours.

These companies generally do not provide elite expertise, because the kind of law firms that buy from a vendor just because they offer convenience generally are not very discriminating about quality. What usually happens with Chinese translation is that translation companies in China offer outsourcers outrageously low rates that cannot possibly be fulfilled without fraud, and the outsourcer finds the deal too good to refuse. The law firm clients of such outsourcers, particularly the one I worked for many years ago, would often continue to use an obviously fraudulent translation outsourcer even after they have given work with serious quality defects. Some large law firm associates fluent in Chinese have complained to me about the terrible quality of their firm’s preferred translation vendor. Law firm management should take care to survey bilingual employees for concerns about translation quality; in my opinion, if an associate knows the law firm is violating its ethical duty to supervise nonlawyers, then the law firm has clearly violated its duties towards clients.

Less-known strengths

From my perspective, the strength of a large outsourcer will usually be that they have a large database filled with the names of translators and can contact people other companies may not have easy access to. Most importantly they have a substantial list of native English-speaking translators, probably about 15-20 in total, and thus, with a good amount of pressure, will agree to put qualified people on a very large, very important project. However, a translation expert will have to watch them like a hawk to get good service, since in the translation industry, it’s very profitable and easy to sell substandard service. The situation is much like with construction contractors: the client doesn’t necessarily know or have the means to find out what exactly the general contractor is purchasing on your behalf. A second less-known strength is that with their large databases, these companies can also easily fill needs for indigenous languages with few speakers, particularly African and Native American tribes. Small outsourcers often buy indigenous language translations from the largest companies to prevent their client from being poached and to give the impression that they have full-service capabilities.

Conclusion

For most clients, a translation outsourcer will simply take your money and light it on fire. That’s because the role of the outsourcer in translation is not to service small “courtesy” projects but rather to handle the extremely large projects of highly sophisticated clients who themselves are experts in the translation industry. Generally, the relationship differs little from that of a law firm hiring temporary employees to staff a client matter. Their large databases of contacts make them an effective partner for delivering manpower, useful for a sophisticated buyer who can utilize their services effectively.