The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act is slated to be signed into law soon, but the American apparel industry says it will “wreak havoc” on their business by creating a rebuttable presumption that all goods originating in Xinjiang are made with forced labor. Reviewing what was already published about the history of the forced labor controversy, I discovered that the Chinese translation used during the early reporting on the program did not at all match what they were being translated into English. This seems to have resulted in a cascading effect, making bilateral dialogue about the issue fundamentally impossible and resulting in an avoidable escalation of the US-China trade war. If the translations used for the conflict matched up with reality, it may have been possible to resolve the conflict through dialogue and legal compliance controls.

Language of Early Reports

My hypothesis is that human rights groups focusing on forced labor allegations deliberately used misleading translation for many years in order to draw attention to their foundations, to the point where translations on this topic are fundamentally misleading. Reporting on the Xinjiang Cotton controversy goes back to about 2015, centering on officials’ description of the need to “reform” (gaizao) terrorism-affiliated populations. A common source of information aggregating media sources, Wikipedia, list a quote from a human rights organization that uses a misleading translation of Chinese officials advising Uyghurs be “educated and reformed through concentrated force […] Release the 70% who just go along, reform the 30%.” The organization reiterates later, ‘The regulations lay out policy directives for detaining and disappearing Uyghurs and other minorities in camps for indoctrination, “re-education,” and “reform.”’

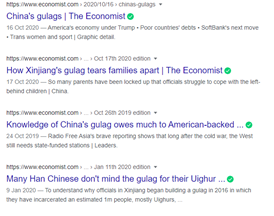

The source language for ‘reform’ and ‘re-education’ in these sources is apparently gaizao, also a shorthand expression for laodong gaizao or laogai, which most sources misleadingly translate as the menacing “reform through labor” or “gulag” (the Economist). Even if official sources call them “training centers,” numerous media reports already identify them as the same as Laogai, which they misleadingly define as ‘forced labor.’ Therefore, to break down the communication barrier surrounding the Uyghur internment allegations, we must correct more foundational issues with Laogai mistranslations.

Wikipedia on Laogai describes the nature of the program as “Forced Labor as a means, while Thought Reform is our basic aim.” The quote is taken from a Laogai activist, a mistranslation that is clearly a tie-in to the famous book on brainwashing, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism, which is at distinct odds with the intended meaning of those speakers and unusually exotic language for prison practices also common in the United States. The real meaning of the Xinjiang officials’ statements is found in an earlier academic survey by Professor Liu Liu:

“What is Laogai? The word “Laogai” is a portmanteau of Lao “labor” and Gai “corrections,” creating an attributive expression. Linguistically, we understand that “labor” is the method, while “corrections” is the goal. In other words, the goal is to rehabilitate prisoners through labor to allow them to turn over a new leaf in life. “ (Translated from Paragraph 5)

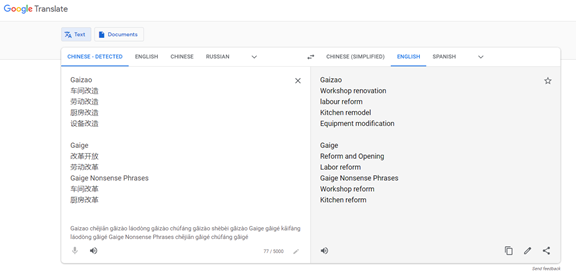

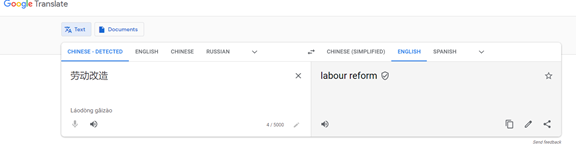

Looking at the word itself, we actually see that Wikipedia’s translation sourced from a Western academic does not include the phrases “thought reform” or “forced labor.” Contemporary Chinese sources discussing the language of these policies actually characterize it in idealistic tones. This is because the word for “reform” here as a Chinese legal translation for gaizao is quite misleading, since the Mandarin word for “reform” is gaige and translators never use the word in other contexts. This mismatch issue can be seen in Google Translate, a dictionary aggregator:

In Google translate, two totally different words, Gaizao and Gaige, are both translated to labor reform even though they mean radically different things. This is because human translator input locked the penal labor translation to “labor reform” as a verified translation:

In the following sections, I closely inspect what the Chinese word behind the “reform” or “reeducation” language—Laogai—refers to in reality, and it quickly becomes apparent that the “reform through labor” translators are misleading and should be abandoned. Instead, the normal English expressions should be used to properly inform the reader, not exoticized phrases like these.

What is Laogai, really?

According to the China Ministry of Justice’s statements, the purpose of Laogai today is similar to that of other countries’ penal labor programs:

“Prisons enforce criminal penalties for the government, with the goal of correcting prisoners into law-abiding citizens to ameliorate criminal recidivism.” (Law translated from official source)

The “correctional” nature of the laogai system is essential to its operation. According to prison official Wang Lijun:

“The three main criminal correctional methods include supervision, education, and labor. Among them, labor is considered the most important correctional method.” (Law translated from paragraph 2)

American standards as found in the Texas Criminal Justice Offender Orientation Handbook, go further than “education”—they explicitly describe mind control programs (“cognitive intervention”), and threaten inmates with longer prison sentences if they do not provide cheap labor. This system of credit-for-labor is also the means of compelling labor in Chinese prison protocols:

“The assessment is divided into correctional education and labor for a total of 100 points. Among which, a maximum of 65 points is allocated for correctional education and 35 points for labor.” (Law translated from Section 6)

China also has prison industries, according to research by Jiang Xiaoxian:

“The Chinese Prison Industry Corporation is a recent development in China’s prison system reform. It’s a wholly state-owned entity that manages prison industries within each province via provincial subsidiaries. The prison industry corporation is a production organization that exists in symbiosis with prisons and provides jobs and locations for penal labor.” paragraph #1 (abstract):

Like the US system, Chinese protocols provide that all convicted criminals are eligible for Laogai unless deemed unfit:

“Section 9 Prisoners deemed unfit for work due to their age, physical disabilities (excluding self-inflicted), or serious illness shall be assessed based on the correctional education component and the full 100 points for the month shall be allocated to education. “ (Section 9)

While penal labor is compulsory, I can find no policies authorizing forcing prisoners to work in a manner that differs from the Texas correctional standards. As the following section shows, merely compelling labor does not create forced labor as defined in anti-slavery policy, so neither the Texas nor Chinese policies shown above authorize forced labor. However, this assessment requires a legitimate distinction between slavery and penal labor.

Slaves or Prisoners with Jobs?

One of my favorite scenes from the movie Thor: Ragnarok is one where Jeff Goldblum’s character objects to the word “slaves,” and instead insists on using the euphemistic phrase prisoners with jobs. This was a brilliant parody of the real world United States school to prison pipeline issue, which is accused of being a vehicle for the enslavement of African Americans. The relevance of Hollywood discussing the issue is that the distinction between penal labor and slavery is very difficult to make and of great urgency, because if anyone is falsely convicted of a crime due to a less than perfect legal system, then labor mandated of them is substantively enslavement.

This raises a question: how does the law distinguish between slavery and penal labor? The distinction is actually highly arbitrary. In the United States, the Constitution defines the distinction by saying anyone afforded due process of law and convicted of a crime may be required to participate in labor programs, and it does not constitute slavery. The United Nations standards would characterize American jury duty and penal labor as permissible compulsory labor. American and British practice has long considered labor coerced by threat of detention penalties as legitimate, even for non-offenders such as military conscripts. American law has even permitted long-term detention of innocent migrant children who committed no crime. In practice, global society labels unacceptable practices as slavery when torture is used to force labor, and is essentially neutral about detentions.

Legal definitions of forced labor tend to be incoherent, and there is no definition for either Penal Labor (laogai) or slavery under Chinese law. Society does, however, have norms for what constitutes slavery and are quick to apply the label “forced labor” to it. In China, this was made obvious with the 2007 slavery scandal, where thousands of adults and even children in Shanxi were kidnapped, and a combination of torture and murder was used to force them to work as slaves in illegal brickyards. Society was shocked, criminals punished, and in response to the scandal, the All China Lawyers Association made this recommendation to define slavery:

“Given the difficulty and complexity of transforming Chinese society, the size of the country, regional differences, and cultural and customary diversity, slavery needs to be clearly defined in Criminal Law to prevent slavery, improve the rule of law, and protect human rights.”

Legislators never determined how to define slavery or Laogai, and therefore China has used custom and practice to define employment, slavery, and penal labor. Prison official Wei Zhiyu describes the current practice:

“From a legal perspective, penal labor is different from regular work. Prisons do not employ prisoners and there is no employer-employee relationship. The prisoners’ labor is a compulsory legal duty. The goal of prisoner labor is corrections. The labor program is merely one of the methods used by criminal justice agencies to rehabilitate criminals.” (Translated from Paragraph 2)

Before the Xinjiang cotton scandal, not much attention was given to the Chinese law distinction between correctional labor and forced labor. In light of US/EU sanctions threats over Xinjiang cotton, one prominent Chinese lawyer, Ma Jianjun, has expressed concern about past scandals of corrupt organizations using slavery and the possibility of its re-emergence in China, but argues that ad hoc standards should be used in European Union agreements because penal labor as practiced internationally can be hard to distinguish from slavery:

“Looking at the development of employment in China since the reform and opening up in 1978, as well as the above regulation, there are no current cases of forced labor due to government administrative action. However, cases like the 2008 Chinese slave scandal in Shanxi cannot be completely ruled out. This is the main reason why the Chinese government is confident in its commitment to the European Union (on the difference between penal labor and forced labor, which may need to be further defined by the Chinese government during their performance of the Agreement with the European Union.)” (Translated from Paragraph 8)

I disagree with Ma Jianjun that slavery (forced labor) and penal labor (compulsory labor) are hard to distinguish. Difficult only arose when Mandarin legal translation into English was used; the Chinese originals of the evidence presented do not describe any intent to create a system of chattel slavery or indentured servitude, but rather a highly idealized corrections program designed to prevent terrorism. This is made especially clear if the historic etymology of the Mandarin legal terminology is examined.

Historical Intent of the Language

China adopted a new word “Laogai” to emphasize reform of prisoner slavery under the medieval Laoyi system. Laoyi is an ancient word dating back to the Qin dynasty. Laoyi servitude was traditionally assessed against criminals and authorized the use of torture to force labor on public works. The reason mainland China uses the word “Laogai” is that socialists in the 1930s wished to create a new social-minded prison labor policy emphasizing “gai” (corrections), thus emphasizing that the prisoner is being helped, and not exploited as a resource. Hu Kaiyu summarized the ancient Chinese law on this point:

“Penal servitude, usually just referred to as incarceration, was also provided for in the laws of the Qin Dynasty. Prisoners would be required to perform hard labor as a penalty along with a definite loss of personal freedom. Penal servitude was widely used in Qin Law as a traditional Chinese penalty that was necessitated by the level of the country’s development at the time.” (Translated from page 17)

In global prison reform efforts, prisons generally continue to operate according to relatively medieval ways of thinking despite progressive policies. That does not change what the meaning of penal labor in itself means, but rather implies that the system failed to live up to its ideals. Like other societies, China has a story to tell about overcoming institutional resistance to prison reform, but the sad state of translation has muted the storyteller.

Implications for translators

Dialogue about Xinjiang Cotton should have focused on ensuring institutional compliance with the rule of law and legal compliance programs for exporters. Instead, Chinese legal translation distorted the meaning of the program so badly that discussion about rule of law issues was totally impossible. A central culprit is blindly using the phrase “gulag” or “reform through labor” instead of facing up to the difficulty of a genuine meaning-based translation.

Some anti-China translators may object that the “gulag” translations are justified as closer to the “ultimate truth.” However, even if the translator believes the euphemistic language to be inconsistent with the ultimate truths, the use of euphemistic language in itself is actually a very important Chinese legal translation issue and is one that should not be distorted by the translator even if a highly contentious geopolitical issue is involved. What happens when translators remove the euphemistic elements from a language as done by numerous articles in The Economist?

Generally, the proper way to confront euphemistic language is through accusations of dishonesty, at which point the dispute is about non-compliance and not policy itself. Erasing euphemisms makes it impossible to confront legal compliance shortfalls or corruption, and turns debate into a shrill screaming match.

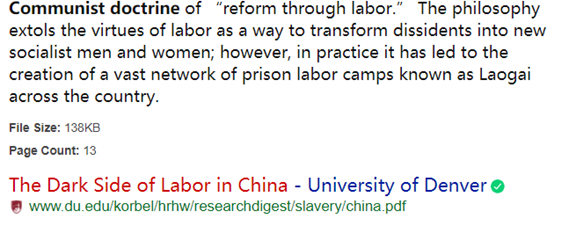

Pro-China translators insist that using an invented phrase “reform through labor” that does not occur in English allows for imbuing the text with a distinctively Chinese meaning, which they feel is a patriotic act. Actually, inventing new nonsense phrases is the same as erasing euphemisms from the Chinese legal translation, because most news reporting and academic reviews tend to focus on negative events and not positive stories (called “muckraking”), the result is books like Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism redefining the invented English phrase according to its worst abuses. This can be seen where the University of Denver files the topic “reform through labor” under “slavery.”

As someone who reads the Chinese original, you might wonder how I feel about the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. My opinion is creating a presumption of guilt for an entire ethnic homeland based on mistranslated sources is unjust because justice requires parties be presumed innocent until proven guilty. Instead, lawmakers should consider use of respected American law compliance monitors backed by American Translator Association certification to provide independent verification about the truth of manufacturers’ anti-slavery compliance claims.

Conclusion

Use of highly unscientific translation practices has greatly inflamed the Xinjiang cotton controversy and bilateral relations between the United States & Europe on one hand and China on the other. The conflict has been further aggravated by sanctions and counter-sanctions, and instead of coming closer to mutual understanding, each side has become even further estranged from the other. Translators can contribute to a positive resolution by abandoning misleading Chinese legal translation practices and ensuring each side is fully capable of understanding the other’s meaning.