Chinese translators have long since been incorrectly translating the word qiye, usually meaning “for-profit business organization” into the English “enterprise,” causing widespread confusion among international readers. The word qiye was originally derived from the Japanese word meaning “a business organization,” and Wikipedia currently links both languages to the word “business.”

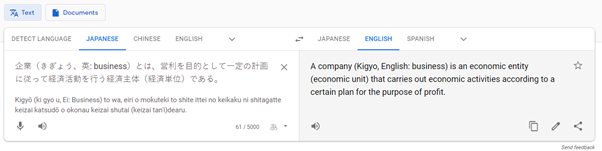

The word is written the same way in both languages but translated to English differently. Translation references will generally correctly translate the same Japanese word to “company” following SEC guidance, but if you switch Google Translate to Chinese, the same word is translated as “enterprise.” You can verify this by copying other language content from Wikipedia into any free online machine translator:

The Japanese dictionaries give correct English words for these terms:

If you switch to the Chinese dictionary in Google Translate, the two overlapping terms above, the word “entity” change to “subject” and “company” changes to enterprise:

If you switch to the Chinese dictionary in Google Translate, the words “entity ” and “company” in the overlapping terms change to “subject” and “enterprise.”

Japanese-English and Chinese-English dictionaries give different answers, because the definition in Chinese-English dictionaries is wrong and nobody has thought to verify its accuracy.

The reason the wrong word is used in Chinese dictionaries is that a hobbyist Chinese Marxist translator translated a Bolshevik Revolution term for Communist production units, (soviet enterprise, to the Chinese word for business organization (qiye) in the 1920s.

The reason the wrong word is used in Chinese dictionaries is that a hobbyist Chinese Marxist translator translated a Bolshevik Revolution term for Communist production units, (soviet enterprise, to the Chinese word for business organization (qiye) in the 1920s.

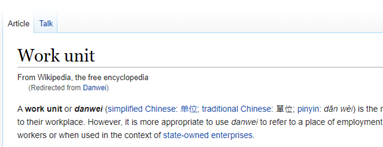

Even though China did develop its own version of the soviet enterprise during the 1950s, known as a danwei, it was word-for-word mistranslated as “work unit.”  For a deeper understanding of why these 1950s translators made such incoherent mistakes, the best-selling history book Tombstone by Jisheng Yang includes a comprehensive analysis of professionals’ thought processes at the time. A generation later, Wikipedia’s hobby translators noticed that the article explanation for the Chinese word actually matches the English word for business much more closely. However, since international information resources like Wikipedia are not accessible in China, the translation industry never noticed the issue, and this, and thousands of other mistakes, have since gone uncorrected. Thus, all the major dictionaries and even Google Translate still list the wrong translation.

For a deeper understanding of why these 1950s translators made such incoherent mistakes, the best-selling history book Tombstone by Jisheng Yang includes a comprehensive analysis of professionals’ thought processes at the time. A generation later, Wikipedia’s hobby translators noticed that the article explanation for the Chinese word actually matches the English word for business much more closely. However, since international information resources like Wikipedia are not accessible in China, the translation industry never noticed the issue, and this, and thousands of other mistakes, have since gone uncorrected. Thus, all the major dictionaries and even Google Translate still list the wrong translation.

A lack of information resources for Chinese translators

The translation of the English word “enterprise” into qiye illustrates how Chinese translators have little choice but to rely on incorrect dictionary entries to complete translations. In linguistic theory, a translator should be looking at authentic native-English sources to determine what an English word means, not potentially wrong dictionaries. But if a translator in China uses Baidu to search for “enterprise,” they will be presented preferentially with Chinese advertisers’ results:

Thus, the Chinese internet and media environment isolates translators from exposure to English culture.

In entertainment, the team of translators CBS hired to translate the name “Starship Enterprise” from the original Star Trek show in the 1960s translated it as the Qiye, meaning “Starship For-profit Business.” The Chinese translation is the only one out of dozens of translations to include such a mistake. Japan translated the ship as the “USS Entāpuraizu,” Korea as the “USS Enteopeulaijeu,” Russia as the “USS Entyerpraiz” (notice how they are all start with Ent-), and only in China was it translated as the “USS For-profit Business”: the Qiye. A plausible explanation is that translators were too terrified of rocking the boat during the cultural revolution.

When Star Trek: Enterprise was produced by UPN, the name of the Enterprise was accurately translated to a word meaning the USS Enterprise, which is very aptly translated and sounds good in Mandarin. Wikipedia and Baidu Baike both use the previous name for the USS Enterprise. But the CBS translators went back to the previous name “Qiye,” and perhaps with some justification. Wikipedia and Baidu point out that during China’s modernization in the 1990s, the English meaning of the word “enterprise” was forced into Chinese through the translation of enterprise computing and enterprise applications, which used the word qiye incorrectly, and the new meanings have since been accepted as an evolution of Chinese.

Seemingly bizarre decisions like this are not unheard of in Chinese translation. This is also why China renamed the “China Navy” to the “China Army Navy” in 1949 and why the Citibank bank branch I visit is called the Shanghai Hongkou Sub-branch. Citibank probably knows its locations are not really called “sub-branches” but doesn’t want to offend local banks in China. Generally, top management has no idea that this extreme authoritarian logic is dominating their Chinese translation process or that the people responsible for their translations are throwing their money into a shredder without even thinking about it.

There is no “enterprise”

The English word for “enterprise” means a “project or undertaking,” for example, a starship that undertakes voyages to where no one has gone before. Meanwhile, the word translated as “enterprise” in Chinese (qiye) started out as a very specific economics term imported from Japan, meaning a “for-profit organization that provides goods and services to the market to create social utility.” The word absolutely does not mean “enterprise” as we understand it in English: and this causes a fascinating ‘bug’ in Chinese legal translators’ brains. For instance, the phrase “criminal enterprise” is a core criminal law concept in both American and international law and widely reported on by media outlets across the globe:

However, it is impossible for a typical Chinese translator to write “criminal enterprise.” Therefore, amazingly, despite the current crackdown on criminal enterprises in China, no Chinese state media has ever reported a Chinese case (i.e. not foreign) involving a “criminal enterprise”:

Notice how all uses of “criminal enterprise” in Chinese media are copied from an English source, not translated from Chinese. While the term “criminal accomplice” is translated without a lot of problems from Chinese, China’s equivalent of global anti-racketeering and criminal enterprise statutes felt the need to invent a nonsense term to encompass the concept:

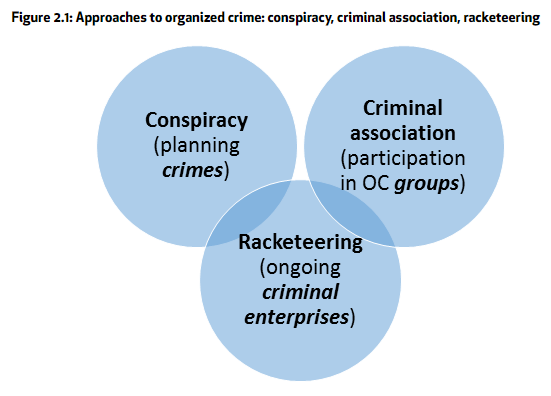

The legislators passing Criminal Code Section 294 into law had dealt in the past with entrenched mafia organizations and desired to criminalize any organization bearing any resemblance to a mafia, instead of having to wait for the organization to start producing Made Men. This is the same exact desire US lawmakers acted on when passing the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. However, because the RICO statute repeatedly uses the word “enterprise,” and Chinese translators’ English education was, for the most part, proceeded by pseudoscientific dictionary memorization, all translators I have tested either interpret the phrase as meaning “business organization” or “criminal association,” a letter crime. They do not reach the same interpretation as shown in this United Nations graphic where a criminal enterprise is an escalation of mere criminal association:

In my observation of Chinese translators using recording software and interviews, the reason for inventing a term like “mafia-like” is because, in the failure to find a foreign equivalent, they conclude that China has invented a new concept with “Chinese characteristics.” Their limited English ability makes it impossible for them to see that other countries, too, passed laws to solve the same exact problem.

Clearly, virtually every time you see the word “enterprise” appear in a Chinese legal translation, the original Mandarin means something totally different. Yet, the word “enterprise” is often used in Chinese translation largely because the original word Qiye, is extremely important in business law.

Qiye: no uniform legal meaning

Although several Chinese statutes define what the word qiye means in highly specific contexts, “scholars have indicated that qiye is an economics concept, rather than a legal concept. A business is any organization involved in production activities.” (translated from this review) There is no uniform meaning; it can refer to different legal concepts in different fields. However, the definition is not standardized, and many statutes apply different definitions of qiye. Professor Meiyan Wang’s study on the issue found:

“Strictly speaking, qiye (business) is not a legal concept. The notion of a business (qiye) was created for finance. However, economists were the first to conduct systematic empirical research on businesses (qiye) as they gradually became a major part of the market economy. Rather than a legal concept, the concept of business has long since been a staple of economics. “

A new parallel usage of qiye began to appear in new Chinese laws translated confusingly as “Sole Proprietorship Enterprises,” “Joint Venture Enterprises,” and “Limited Partnership Enterprises.” Confusingly, these laws simultaneously created two parallel entities, one called a Partnership (geren hehuo) and the other a Partnership Enterprise (hehuo qiye). This raises a question for someone considering doing business in China: is there any difference in Chinese law between a Partnership and a Partnership Enterprise?

Qiye sometimes means a business entity

Why did the word “enterprise” begin appearing in many business organization statutes in recent decades? Statements by lawmakers at the time show a desire to phase out the informal economy by registering non-entity enterprises as business entities. The new statutes add the word qiye to distinguish a business that meets threshold formal sector requirements. During the early days of socialist reform, China passed a number of statutes to create Partnerships and Family Proprietorships (like sole proprietorships, but owned by the family), but these business registrations did not create a separate business entity. Guidance from Chinese courts about who to list as a defendant when suing a Family Proprietorship under the old statutes makes it clear that there is no separate entity:

“Under the Civil Procedure Law: The owner registered in the business license for a family proprietorship shall be the party in litigation. The party shall specify the distinctive trade name (if any) in the legal documents. Joinder of the owner and the actual operator of the business is required if the proprietor registered in the business license is not the actual operator of the business.”

When China modernized its business entity statutes to bring informal sector business in line with corporations and companies, it added statutory and regulatory text stating that these business organizations now create a separate business entity. The Chinese courts have this to say about what party to name when suing a sole proprietorship:

“The dispute on the sole proprietorship’s standing in procedural law is easily resolved once the legal status of a sole proprietorship is established. Article 40, Section 1 (1) of the judicial interpretation of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China clearly provides that “a registered sole proprietorship is a separate business organization with independent status.”

The new sole proprietorship statute replacing the older family proprietorship is part of a broader trend of replacing the primitive cottage industry economy, where proprietors worked out of their homes, with a more sophisticated economy with clearly segregated business and residential districts. Thus according to the Zhonggangxing law firm, one of the new requirements applicable in almost all jurisdictions is that each new Sole Proprietorship must now have its own business premises and a unique legal name, which in some jurisdictions, such as Canada, is called the distinctive element of the name.

The next step up in complexity in the new and revised business organization statutes is the Limited Partnership Enterprise statute which, like the above, really means Limited Partnership Business Entities. Under the old Partnerships rule in the civil code, a partnership did not create a legal entity that could be sued but was rather simply a way of jointly apportioning liability and rights among several partners. A new partnership statute was introduced in 2007 with the old partnership law set to expire with the new civil code in 2021. The new partnerships greatly modernized and standardized the partnership law, creating separate entities to participate in lawsuits, and limitations on liability. Congressional Vice Chairman Huang Yicheng’s explanation of the need for a new law to supersede the old captures the spirit of the legislative process behind the new partnership laws:

“[…] compared to companies, partnerships have an expedient formation process, flexible funding, a simple organizational structure, and easier management. Partnerships also play an important role in economic development, job creation, social diversity, and improving quality of life. However, they currently face numerous issues: partnerships have uncertain title to property, occasional interruptions to the regular business operations, insufficient self-regulation in partnership production and operations, no standardized organizational structure, uncertain assumption of liability, and undefined partner rights and obligations. A partnership law must be enacted to solve these issues and allow for the continuous development of partnerships.

Third, current partnership law is too skeletal and does not provide for standardization and consistency. Moreover, some rules do not meet the needs of the market, thus increasing the need for legislation specifically governing partnerships.”

Why are the new partnerships called “Partnership Qiye”? The lawmakers included this language in all statutes that enabled business organizations to exist as an independent business entity, but moreover included the label qiye to indicate a move toward business law reform following the advice of economists. Hence, in this context, the qiye is used only to refer to formal business entities and the point of using the word is to exclude informal business organizations. This is actually the opposite of how United States law uses the word “enterprise,” for example with “criminal enterprise” and “new commercial enterprise,” where it is used specifically to include informal business so as to cast a wide net and capture all kinds of economic activity.

Chinese translators deliberately make mistakes

Why is there so much nonsense English coming from Chinese legal translations? Chinese translators deliberately leave in mistakes to save time on looking for the correct answer, thus earning more per hour than if they did the work diligently. When I first started teaching translation, many students would intentionally put down nonsense or invented terms. When I asked why they did so, they expressed an expectation to me that they can deliberately put in completely wrong translation terminology, and that the foreign reader will carefully study their fictional language to learn what it “actually” means. This not uncommon opinion holds that being a good translator means copying older translators, even if you know those answers are wrong. Needless to say, this never actually happens in reality; international businesses expect their people to get things right. Students only developed a commitment to using the correct answers when I began including neurolinguistics and systemic functional linguistics in the curriculum, but these techniques are too difficult for more than a handful of translation program candidates to apply. Most students will drop out of the program rather than face the difficulty; thus, there are few qualified translators in this field.

Conclusion: What does a translation mean?

If you are ever presented with an English translation of any kind of Chinese legal or business documentation that includes the word “enterprise,” you can be sure that the word has been mistranslated in almost every case. You need to throw that translation into the garbage can and start again to avoid any possible serious consequences from using an unreliable translation. Chinese language is highly reliant on context and, depending on the situation, the relevant legal professional would define the source term qiye as variously meaning business, company, or business entity. In legal contexts, however, the word absolutely does not mean what enterprise means. A competent translator should recognize the complexity and nuance of language and face up to it, not turn in shoddy rush work that the client has to pay for.