The concepts and practices related to translation are usually confusing to lawyers, who generally apply the single label “translation” to refer to several loosely related but distinct practices—translation, interpretation, and localization. This is normal for anyone who lacks language service industry experience but, in practice, severely hampers corporate legal departments and law firms’ ability to do effective work internationally. A major pain point over the years has been contract translation, which in Chinese to English translation has caused such severe problems that numerous articles warn businesses about potential Chinese translation “disasters.” In recent years, numerous businesspeople have even been arrested over translation-related complications. These totally unnecessary problems are a result of bad legal translation services, and in this article, I’ll explain how Chinese contract localization best practices can be used to effectively eliminate unnecessary legal risks.

What translation means for lawyers

The professional vocabulary used in the language services sector is not very well understood by most lawyers, and indeed when I was in law school, I did not really know the difference either. This calls to mind when Adlai Stevenson told the USSR ambassador, “don’t wait for the translation” and to instead answer his question about Soviet missiles in Cuba: what Mr. Stevenson really meant is an interpretation, which is not a translation because the accuracy rate of an interpretation should be expected to be fairly low on account of the high speed with which the work is accomplished. A lawyer relying on interpretation does not get the whole story, although interpretation is indispensable for practices such as the FCPA, where in-person interactions are necessary to get to the truth of the matter. Another important vocabulary item for lawyers to master is localization, which is the subject of this article.

Localization was initially developed for marketing in response to disasters such as KFC’s infamous Chinese “eat your fingers off” campaign, an embarrassment that led KFC to become the most successful marketing localizer in China today—indeed, China’s biggest restaurant chain. KFC’s China localizers also smartly provided its Chinese customers with disposable plastic gloves to avoid the possibility of customers even needing to lick their fingers. There are also important cultural differences to take into account in Chinese contracts. For example, China currently does not adopt the doctrine of liquidated damages, and if you try to liquidate uncertain damages, a judge might consider your contract unfair. This kind of content needs to be localized according to local business practices, which in China are hugely different from foreign practices.

Another problem that arises is if you just ask a local translator, a law firm, or even in-house counsel to translate a contract for you, the results are usually fairly absurd. For example, I have seen an American Fortune 500 company’s in-house counsel in China translate a garden variety shipping contract into Chinese using a huge variety of Chinese vocabulary that, in this specific combination and context, absolutely never occurs in real-world Mandarin Chinese contracts. In fact, when searching through a corpus of 100,000 form contracts used by real law firms in China, not a single hit occurred. The in-house legal counsel’s process of translating the document was to simply look up each word in the dictionary and add the corresponding word appearing in the dictionary in that space. While each word technically does map to another dictionary term, in the event of litigation, no judge could possibly understand this contract. Moreover, Shanghai judges have complained quite a lot about these translated contracts in the past, to little avail. However, when back translating the contract, the English version is basically a perfect copy of the original.

What happened? The in-house counsel’s idea of a translation was to encrypt the contract into a series of Chinese symbols, with the back translation serving as the decryption key. In other words, the Fortune 500 company’s in-house counsel is really just paying for a fantasy of good legal risk management. If sued in court, all of the legal protections in the contract would be thrown out—without the company really ever realizing it, so powerful is the illusion of mistranslation—and they would conclude that Chinese courts treat Western companies unfairly. Instead of buying into the stereotypical, false narrative of rampant anti-Western discrimination in Chinese courts, I invite companies to consider using Chinese legal document localization to better ground their risk management.

Steps for Chinese Contract Localization

In my opinion, contract localization should be done differently from marketing localization because the contract will be executed in China, which makes a huge difference. Thus, the process should be more complex than what is done for marketing content localization in that local lawyers are needed as part of the process. The three main phases I’d recommend for the process are as follows:

First, the document is translated into Chinese by professional Chinese legal translators with the goal of facilitating localization. This can save a great deal on legal costs when drafting the executable version of the contract, in the same way that a form contract, letter of intent, or a term sheet prepared by a broker for a transactional contract saves lawyers a lot of legal costs on preparing the relevant legal documents. Law firms do frequently translate contracts, but usually at a fraction of the speed that translators do, along with the immense overhead of running a law office. So, a professional translator would cost a quarter of what lawyers might.

Moreover, the quality of the work is much higher. Specifically, a lot of Anglicized contracts in China are drafted in that way because the lawyers don’t really understand what the contract is trying to say. Many contract terms get mangled or jumbled as a result. Foreign language expertise and local Chinese law expertise are mutually exclusive skill sets for local lawyers: an hour learning how to translate is an hour not spent mastering the law, and only a handful of really expensive geniuses simultaneously do both. A native Chinese legal translator will almost always need to consult with native English colleagues to accurately understand certain expressions at a native level.

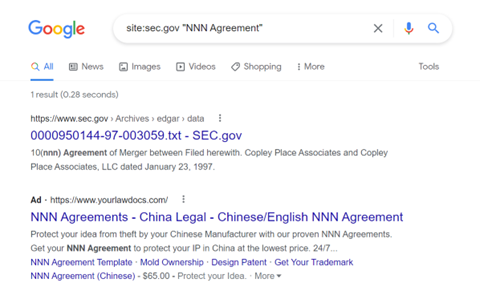

Second, the Chinese-language version of the originally desired contract is used as a form contract by the local lawyers to design an appropriate local contract that preserves the Western company’s intended way of doing business while ensuring that the contract is appropriate for use in China and one that, in the event of a legal dispute, a judge would understand and apply. A good example of why this is important can be found if you Google “NNN Agreement” in both English and Chinese (you can also search SEC.GOV to confirm this). In English, you’ll see lots of results from law firms hawking NNN Agreements and proclaiming these are essential in China. However, the Chinese results about NNN Agreements basically all say nobody in China has heard of these, judges have no clue what these are, companies are mystified by them, and they seem to have been an invention of lawyers in America, apparently, something that American lawyers came up with based on American laws and then just translated to Chinese without any adaptation. If you don’t speak Chinese, you can search the SEC’s database of legal documents of listed corporations in translation to verify that nobody is using these agreements at all, despite listed Chinese companies having plenty of confidentiality provisions uploaded to the SEC EDGAR database:

You do not want to get into a situation where you are going to China to manage risks and use legal concepts totally unknown to Chinese judges. An unscrupulous business partner could easily exploit such Anglicized Chinese contracts and the confusion they cause judges to argue that the two parties really don’t have an agreement. When that happens with NDAs involved, your intellectual property protections could also be totally waived. This particular step of the process I’ve recommended ensures that you can deploy that local knowledge to protect from risks and avoid the problem of Anglicized Chinese contracts.

Third, contracts adapted for local use by Chinese lawyers should be translated accurately into Chinese using the certified translation process and then formatted as bilingual documents following local China customs—noting that the Chinese version alone applies. This approach involves several key strategies. First, you do not want the English document to apply because a rogue translator in China could easily mislead the court about what the English version says, in which case the translation would need to accurately anticipate what an incompetent translator would do with it. That is, it would need to be written in Chinglish, which defeats the whole point of translating the contract to English to begin with.

The third phase of the contract localization project recommends the use of certified translators providing a certified translation for the simple fact that the Western company needs to know what the contract says. In fact, the Western company needs to know what local employees are generally doing. A good example of this is McDonald’s in China. Most Shanghai restaurants, even expensive ones, have a “B” sanitation rating. However, Shanghai gives every McDonald’s location I’ve checked—over 30—an “A” rating. McDonald’s knows and audits what its employees are doing. Rigorous attention paid to hand-washing and expiration dates on labels earned McDonald’s top marks from Shanghai’s food safety regulator and subsequently earned the trust of a local population terrified by local food safety scandals, such as the Fonterra Foods scandal. In the Fonterra case study, New Zealand executives admitted that they did not know what was going on with their China operations when local staff knowingly added poison to infant formula.

The Harvard Business Review’s top expert on the subject once wrote in the HBR that the supreme level of delegation is to give your reports flexibility to make the best decision and report accurately on it. If your business document is mistranslated, you’ll have crossed the line from McDonald’s to Fonterra. Both sold dairy products sourced identically, but one’s lack of control resulted in poisoning babies with the same chemical compound used to make the Mr. Clean Magic Eraser. Try putting one of those in a blender and drinking it!

The role of the ATA and CIOL-certified translators, and what the organization specifically tests for, is the provision of a translation service that is totally accurate as to the facts and the law. The federal government prizes this skill level and authorizes the highest pay packages for them, valuing them at a similar level as retired Generals serving as strategic consultants (the evidence is too detailed to go over here, but feel free to e-mail me to learn more). In general, the reason for the high value is that if you accurately know what is happening in China, then you can make good decisions—and Jeff Bezos argues that the fundamental role of an executive is to make good decisions. The certified translator is the person who enables an international executive to make good decisions. In the context of a contract, a Western company’s executive cannot assume that local staff will be enforcing its contracts appropriately.

There is a huge agent-principal problem when acting over such huge distances. Even if staff is well-trained in legal and compliance, there are frequent issues like supplier kickbacks, fraud, and theft. Otherwise, you’ll get problems like the US retailer who 60 Minutes accused of selling toxic floorboards. The way you avoid those risks is to have local lawyers ensure your contract has the appropriate enforcement mechanisms for this kind of scenario, and to use the ATA-certified translation process to ensure that your company can make good, well-informed decisions.

Summary

In this article, I introduced a three-phase process by which a company can effectively localize its English contracts for use in China. First, a contract is translated into Chinese for a local Chinese law firm to adapt. Second, local lawyers complete the adaptation process for localizing the contract. Third, the new localized contract is translated into English. This strategy avoids two major problems with international contracts used in China. Specifically, the contract avoids using Anglicized Chinese, which is largely useless in Chinese courts. Additionally, international executives and counsel will be able to accurately understand the content of the Chinese contract and make good decisions to manage legal risks.

2 comments

Thank you very much for writing these articles. I have learned them. I am a poor Chinese translator, and you give me some confidence. I am completely agree with your view.

Thank you.