Readers of Chinese legal translations usually have to navigate a maze of confusing direct translations of Chinese syntactic words into substantive English words. A leading example is where the word “relevant” (youguan/xiangguan 有关、相关) appears within legal Chinese. This often appears in things like “relevant laws,” “relevant department,” or “relevant persons.” Diplomats often talk about “relevant countries” when scolding American politicians for saying something politically incorrect. The way in which it appears in translation, however, is totally different from how the words are used in natural English language used for communicative purposes in the English-speaking world.

In the legal context, Chinese lawyers say they use the word youguan (“relevant”) with the intent of limiting the scope of what a word can refer to. In this sense, it functions much like the English word “the” (which has no direct correlation in Mandarin). For example, when the translation talks about “relevant departments,” Chinese lawyers explaining exactly what they mean in the original say that they are referring to a government agency authorized or empowered to take a particular action to resolve the facts presented. In English regulatory law, this is typically referred to as the “appropriate agency.” For example, the appropriate agency to investigate the scene of a workplace accident is the workplace safety agency, and the local law enforcement agency may also be appropriate.

The English word “relevant” means something significantly different, and there is a reason that American lawyers avoid the phrase “relevant laws” and use “applicable law” instead. As in most everyday usage, “relevant” in the legal context means “having significant and demonstrable bearing on the matter at hand” (Merriam-Webster). For example, lawyers do use “relevant facts” when referring to facts that have a significant bearing on the case. However, when the phrase “relevant law” is used, it typically appears in reference or educational titles and means that any law significant to that specific topic is included. For example, secured transactions is relevant law for bankruptcy. Chinese dictionaries actually list 15 words all translated to English as “relevant,” and about 90% of the time they mean what another English grammatical or syntactic word means.

An interesting case concerning “relevant” and other Chinglish translations that can be observed in daily interactions in China, like “corresponding,” is meetings or conferences between speakers of officialese and people using plain Mandarin Chinese. A lot of functional words in Chinese exist solely to increase the formality and register of the language used. A translation in a conversation used in this matter might look like this:

Official: It is recommended that corresponding persons apply relevant policies of virus control.

Business: “I’ll get the right person to apply the virus control policy.”

In this sentence, why would the translator use the phrases “corresponding,” “relevant,” and “it is recommended” instead of how a US official would talk, i.e., “Qualified personnel should apply the virus control policy?” The translator is attempting to convey that the language is highly formal, yet the reader wouldn’t understand any of that because a typical reader will have never seen these words used in that way. Thus, the language looks more like a word salad than a highly formal and crisp expression, largely the opposite of the original.

Solutions for Legal Translation Projects

The solution to the problem of directly translating syntactic words is easy to describe but requires a great deal of experience and skill to put into practice. A translator working with a sentence that has syntactic words in it should consider the role of the word used in the sentence and whether it refers to substantive ideas or is part of the syntactic organization of the sentence. If a native English speaker reviewing the sentence thinks there is a lot of meaninglessness or redundancy in the expression, then a lot of purely syntactic expressions were likely translated into substantive expressions. The next step, which is the hard one, is to identify what language or structures in an English sentence correspond with the syntactic meaning intended in the original. This can be challenging because the correct answer might not be a word in English, as sentence structure and sequence can play grammatical roles. Recent research even verified that facial expressions are interpreted to have grammatical meaning, which shows how much content exists outside of the words themselves.

A second big challenge was raised in VWO Quine’s article Ontological Relativity. While an extremely expansive article, Quine discovered that the measure words in Chinese and Japanese refer to linguistic concepts not found in English. For example, “two horses” in English is composed of two language parts, but the Chinese liang pi ma (两匹马) has three grammatical parts, with an additional one referring to textiles, which, if taken very literally, could mean two “kinds-of-things-that-can-have-a-saddle horses.” This deserves some caution: If translated to Chinese and literally translated back, the English phrase “two rivers” may be “two stretches of river,” which could be interpreted as two parts of the same river.

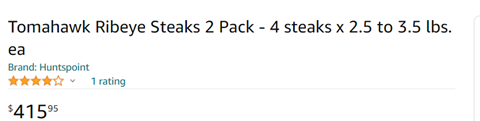

The famous English teaching company New Oriental recently made a similar mistake when translating Chinese into English for its new streaming program. Since cram schools in China were shut down, New Oriental has tasked its English teachers to sell food online during live streams. In a famous recent example, an English teacher shows what appears to be “twelve steaks,” but translates the syntactic part of the expression into English as “twelve pieces of steak.” New Oriental made the mistake of thinking the English expression “piece of steak” is purely syntactic and translated it as such. However, when selling bulk raw steaks, English speakers actually say things like “four steaks” or “twelve steaks,” as is displayed on retailers’ websites, such as Kroger and, below, Amazon:

If someone says “two pieces of steak,” they are generally not talking about how many steaks are going to be cooked and put on a plate. Some may be thinking about a single steak cut into twelve pieces, and a significant number of stock photos do show bite-sized pieces of steak described in this manner. Instead of “pieces,” sales of raw beef are more likely to talk about “cuts.” Syntactically, this is not used like the Chinese measure word to narrow scope—but rather to emphasize that a fine cut is being sold. A case study where this causes disaster in legal translation is the Frigaliment case, about a contract for the sale of meat.

Why are Chinese legal documents being translated into English this way? Historically, about three hundred years ago, some translation theorists proposed that the only way to be truly faithful to a document is to translate each and every word into the target, leaving nothing to the interpretation of the translator. This was an obviously unscientific practice, not unlike medieval medicinal practices revolving around things like elements or humors. In medieval times, every professional practice was in a pretty sorry state—science had not yet developed and, back then, nobody knew what language in itself is or how it works. Nonetheless, the outdated theory was picked up in China and revised into a kind of truism called Xin Da Ya, which I critique in an article here. Today, we have made numerous advances in understanding languages, yet, nonetheless, most Chinese translators continue to resist these advances and stick to ancient ways of doing things. A phenomenon called anchoring bias explains why legal translators keep doing this.

Anchoring Bias

The anchoring bias phenomenon in cognitive psychology explains why so many translators are stuck on using outdated translations that emerged over a century ago, often a result of the incorrect guess of a translator who was working in medieval conditions at the time. This cognitive bias is generally described as the influence on a person’s decision by “anchoring” to a certain reference point. In the law, interesting experiments have been done whereby providing an anchor point to a court can affect the decision a judge reaches. Anchoring affects pretty much every kind of activity, but translation is currently among the most susceptible.

A Chinese translator affected by anchoring bias usually starts out by looking at machine translations, dictionaries, or parallel corpora for suggestions on how to translate something. Typically, for Chinese-to-English legal document translation, the result displayed is going to be something that was haphazardly inserted as much as a century ago. Early legal translators were usually literary and diplomatic translators borrowed to help translate a treaty who, lacking any knowledge or specialization in the field, defaulted to making guesses or word-for-word translations, thus deforming references to regulatory agencies into “relevant departments.” Much of this early work was entered into dictionaries and translation references and treated as gospel by later translators, even if many of the early translators, now in their 70s or 80s, pointed out in more recent years that they totally lacked the tools needed to do effective legal translations decades ago and that earlier works were probably wrong.

Nonetheless, most Chinese legal translators carry forward the initial mistake made by early legal translators, despite these understandings being plainly wrong. Many people object to the strange legal titles and translations created by these misunderstandings. However, a typical legal translator in China will nonetheless refer to dictionaries and parallel corpora, and then fiercely defend the answer found in those references. If two translators check different resources and reach different conclusions, they will often just battle each other on whose anchoring point is correct. In organizations, yelling, coercion, and pulling rank are often involved. And it’s not just among translators; if you have a bunch of lawyers start translating, all that critical thinking talent usually flies out the window. The unique problem for translators is that these resources present no evidence for their conclusions—just naked answers. Thus, Chinese legal translators’ thought process is often just defined by what unsubstantiated answer they first look up.

The Takeaway

Conventional translations of Chinese legal documents translated to English include translation errors where purely syntactic and grammatical words are rendered into English using words having highly substantive meanings. In some cases, these errors were preserved in parallel corpus resources and dictionaries for centuries, despite not making sense or even being very misleading to target readers. Translators today continue to make these errors because of their anchoring bias, that is, they become attached to the first translation recommendation they see even if it is wrong and rationalize its usage despite there being poor evidence that the result is correct. Getting these translations correct requires some cooperation between the client and the translator. The client requesting translation will need to avoid requests for dictionary-based translations, but rather look for evidence-based translation services. When providing services for evidence-based translations, translators should avoid reliance on dictionaries and parallel corpora, and base translation decisions on empirical evidence instead.